Page 20 - GIS for Science, Volume 3 Preview

P. 20

COASTAL VARIATION

The coastline is universally understood as the intersection of Earth’s land masses and oceans. Coastal areas are extremely important to humans, in that approximately half of the world’s population lives within 100 km (62.1 mi) of the ocean.3 The very survival of many human societies depends on the provision of ecosystem goods and services as benefits from coastal environments, and the supply of those benefits is a function of the health of the coastal systems. Highly degraded coastal ecosystems are compromised in their ability to satisfy human needs for food and other goods and services.4, 5 To continue producing important benefits for humankind, coastal ecosystems must be well-managed, and that will require a comprehensive understanding of the types, distributions, ecology, and condition of Earth’s coastal ecosystems. In other words, researchers will need well-documented maps that provide a digital canvas for ecosystems data.

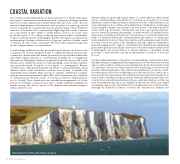

Coastal settings exhibit spectacular geomorphological diversity (as shown in the coastal photos). Coastal classification aims to classify diversity and partition the coastline into distinct units with similar properties. It is expected that similar units will exhibit similar responses to environmental perturbations or management interventions. Classifying coastlines is an application-specific exercise, and coastal systems can be classified in numerous ways depending on the intended emphasis (e.g., geomorphological, biological, socioecological, or oceanographic). Because coastal areas are often densely populated and subject to natural and human-caused disasters, much coastal classification work has been focused on hazards, risk, vulnerability, and sensitivity. Many nations, for example, classify their coastlines using an environmental sensitivity index (ESI), which characterizes the sensitivity of coastal assets (biodiversity, centers of economic production, cultural features, etc.) to oil spills.6 These classifications are intended as management tools for the protection of valuable coastal resources. Most coastline sensitivity classifications include, among other factors, aspects of the physical environmental settings in which coastlines occur.

Characterizing the geomorphological nature of coastal physical environments is key to understanding coastal variation,7, 8 and there is a long history of coastal classification based on physical features. Either sea-level rise or land subsidence can cause submergence of a coastline, and a simple binary classification of submerged versus emerged coastlines was already in use at the start of the 20th century.9 At coarse scales (e.g., thousands of kilometers), and from a geological perspective, tectonic activity is a primary determinant of coastal variation, as explained in the classic paper by Inman and Nordstrom.10 The presence of coastal mountains, the width of continental shelves and continental plains, the existence of volcanic and barrier islands, the location of major river systems—all these features result from the movement of tectonic plates on the lithosphere. This type of genetic classification approach emphasizes the origin of coastal landforms. Classifications emphasizing geomorphological structure and processes have evolved from initial considerations of submergence and tectonic history to include emphases on dominant coastal processes,11 coastal systems,12 and the morphodynamic coevolution of form and process.13

Another fundamental class of approaches to understanding coastal variation deals withhydrodynamicforcingfeatures.Theseapproachesfocusonhowwatermovements shape coastlines. Many coastal areas are underlain by bedrock, which slowly erodes over time due to the actions of water and wind. This weathering process is erosional in nature, and these generally rocky coastlines are classified as erosional. In contrast, the sediments produced from weathering can be deposited in the coastal zone to form depositional environments. The sediments that are deposited along the shore create beaches, tidal flats, and dunes, and the sediments that are transported to the coast by rivers create deltas and estuaries. These coastal areas, built up over the long term from sediment deposition, are classified as depositional. These next images are examples of geomorphological diversity in coastal areas based on substrate type. Although the distinction between erosional and depositional coastlines has

Chalky bluffs at the White Cliffs of Dover, England.

8 GIS for Science