Page 151 - GIS for Science, Volume 3 Preview

P. 151

OCEAN ACOUSTICS

In air, we use electromagnetic radiation to interact with our environment. We use visible light, detected by our eyes, to see, radio waves to communicate, and lasers to determine the range to an object (lidar). Underwater, this electromagnetic radiation does not travel very far because it attenuates rapidly. For this reason, researchers use sound as a tool to study the ocean and acoustics as a way to “see” it. For example, the military uses sound (sonar) to find submarines, and oceanographers use it to measure temperature, salinity, and other properties of the ocean.

Acoustic propagation modeling

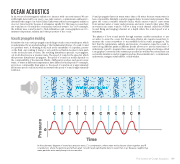

Scientists rely on acoustic propagation modeling to study ocean soundscapes, which is underpinned by an understanding of the fundamental physics of sound. Sound is a pressure wave. A vibrating body, such as the membrane of a speaker, presses on the fluid surrounding it (water or air), and those fluid molecules in turn push on the molecules next to them. The resulting disturbance spreads, or propagates, out in all directions as a pressure wave. The speed of sound is the speed at which this pressure disturbance propagates. The speed of sound in a media depends on the compressibility of the material. Fluids of different properties, such as air versus water, or water at different temperatures, have different sound speeds. For example, air is more compressible than water, so the speed of sound in air is approximately 350 meters per second (m/s); while in seawater the speed of sound is approximately 1,500 m/s.

Sound propagates faster in warm water than cold water because warm water is less compressible. Similarly, sound propagates faster in water under pressure. This gives the ocean a variable refractive index, which causes sound to curve away from warmer water or water under pressure and curve toward colder water. This movement can cause sound to follow a deep sound channel called the SOFAR (sound fixing and ranging) channel, at a depth where the sound speed is at a minimum.

The physics of how sound travels through seawater enables researchers to use acoustics to sense the ocean, but these same physics also require researchers to measure the ocean everywhere to successfully model acoustic propagation. The fact that the temperature, salinity, and pressure of seawater cause the sound to travel along different paths at different speeds allows us to use the travel time of underwater sound to measure these seawater properties using a technique called tomography. Conversely, if the seawater properties are well known, researchers can accurately simulate sound propagation and use these simulations to communicate underwater, navigate submersibles, or find whales.

Water particles

In this

CCCCCC

Time

schematic diagram of sound as a pressure wave, C is compression, where water molecules are closer together, and R is rarefaction, where the particles are farthest apart. Sound travels significantly faster in water than in air because neighboring water particles more easily bump into one another.

0

R

R

R

R

R

R

The Science of Ocean Acoustics 139

Pressure